Mary Queen of Scots remains one of history’s most compelling and tragic figures—a woman of intelligence, charm, and political cunning, yet ultimately undone by the very qualities that made her extraordinary. Her life was a whirlwind of power struggles, betrayals, and personal losses, culminating in a dramatic execution that shocked Europe. This blog post explores her early years, her tumultuous reign, her imprisonment, the conspiracies that sealed her fate, and the legacy she left behind.

The Early Years: A Princess Born into Turmoil

Mary Stuart’s life began in the midst of political and religious upheaval. Her early years shaped her into a resilient yet vulnerable queen, destined for a throne she would never truly secure.

A Royal Birth Amidst Religious Strife

Mary was born on December 8, 1542, at Linlithgow Palace in Scotland, just six days before her father, King James V of Scotland, died in battle. His death left the infant Mary as the sole heir to the Scottish throne, making her queen at just six days old.

- Religious Divide: Scotland was deeply divided between Catholics (loyal to the Pope) and Protestants (led by reformers like John Knox). Mary’s Catholic upbringing would later become a major point of contention.

- English Threat: England’s Henry VIII saw an opportunity to unite the crowns through marriage, proposing his son Edward VI as Mary’s husband. When Scotland refused, Henry launched the Rough Wooing (1543–1551), a brutal military campaign to force the marriage.

Actionable Insight: Mary’s early exposure to war and political maneuvering taught her the importance of alliances—lessons she would later apply (and sometimes misapply) in her reign.

Raised in France: A Queen in Training

To protect her from English aggression, Mary was sent to France at age five to be raised in the court of King Henry II and betrothed to his son, the Dauphin Francis.

- Education & Refinement: Mary received an elite education, becoming fluent in French, Latin, Greek, Spanish, and Italian. She excelled in music, poetry, and needlework—skills that made her a dazzling figure in European courts.

- Marriage to Francis II: In 1558, at age 15, she married Francis, who became King of France a year later. However, his reign was short-lived—he died in 1560 from an ear infection, leaving Mary a widowed queen at 18.

- Return to Scotland: With no future in France, Mary returned to Scotland in 1561, now a Catholic queen in a Protestant nation.

Step-by-Step Tip: Mary’s time in France taught her the art of diplomacy and courtly intrigue. Modern leaders can learn from her ability to navigate complex political landscapes—though her later failures show the dangers of overconfidence.

A Queen Without a Kingdom

Upon her return, Mary faced immediate challenges:

- Protestant Opposition: Scotland was now under the influence of John Knox, a fiery Protestant preacher who publicly denounced her as an “idolatrous Catholic.”

- English Suspicion: Queen Elizabeth I of England (Mary’s cousin) saw her as a threat—Mary had a strong claim to the English throne (as a granddaughter of Henry VIII’s sister, Margaret Tudor).

- Personal Struggles: Mary was grieving her husband, politically isolated, and unprepared for Scotland’s harsh political climate.

Example: In 1561, Mary attended a Protestant service in Edinburgh, a symbolic gesture to ease tensions. However, Knox preached against her, calling her a “harlot” and a “Jezebel.”

Actionable Insight: Mary’s early struggles highlight the importance of building a strong support base—something she failed to do effectively in Scotland.

The Reign: A Queen’s Descent into Chaos

Mary’s reign was marked by poor decisions, scandalous marriages, and growing unrest. Her inability to balance personal desires with political realities led to her downfall.

The Marriage to Lord Darnley: A Fatal Attraction

In 1565, Mary married her first cousin, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, a move that alienated her Protestant nobles and angered Elizabeth I.

- Why Darnley? Mary was infatuated with Darnley’s good looks and charm, but he was arrogant, ambitious, and politically inept.

- The Rizzio Murder (1566): Darnley, jealous of Mary’s secretary David Rizzio, conspired with Protestant lords to murder him in front of a pregnant Mary. This betrayal shattered her trust in Darnley.

- Birth of James VI: In June 1566, Mary gave birth to James (future King James VI of Scotland and I of England), but her marriage was beyond repair.

Step-by-Step Tip: Mary’s marriage to Darnley shows the dangers of mixing personal emotions with statecraft. Modern leaders should separate personal relationships from political decisions to avoid similar pitfalls.

The Downfall: The Earl of Bothwell and the Murder of Darnley

Mary’s reign spiraled into chaos after Darnley’s mysterious death in February 1567.

- The Kirk o’ Field Explosion: Darnley was strangled and blown up in an explosion at Kirk o’ Field, Edinburgh. Many suspected Mary and her new favorite, the Earl of Bothwell, of orchestrating the murder.

- Marriage to Bothwell: Just three months later, Mary married Bothwell, a move that outraged the nobility. They saw it as proof of her guilt in Darnley’s murder.

- Forced Abdication: In June 1567, Mary was imprisoned at Lochleven Castle and forced to abdicate in favor of her one-year-old son, James VI.

Example: The Casket Letters—alleged love letters between Mary and Bothwell—were used as evidence of her complicity in Darnley’s murder. Historians still debate their authenticity.

Actionable Insight: Mary’s downfall demonstrates how scandal and poor judgment can destroy even the most powerful leaders. Transparency and accountability are crucial in maintaining public trust.

The Escape and Flight to England

After a daring escape from Lochleven, Mary raised an army but was defeated at the Battle of Langside (1568). With no other options, she fled to England, seeking Elizabeth I’s protection.

- Elizabeth’s Dilemma: Elizabeth could not ignore Mary’s claim to the English throne, but she also could not let her go free—Mary was a Catholic rallying point for those who wanted to overthrow Elizabeth.

- Imprisonment: Mary was placed under house arrest and moved between castles for the next 19 years.

- The Beginning of the End: Mary’s presence in England fueled Catholic plots against Elizabeth, making her a prisoner of political necessity.

Step-by-Step Tip: Mary’s flight to England shows the importance of contingency planning. Leaders should always have an exit strategy in case of political collapse.

The Imprisonment: A Queen in Captivity

Mary’s years in captivity were lonely, frustrating, and filled with failed escape attempts. Her imprisonment was not just physical but psychological, as she was constantly monitored and manipulated.

Life Under House Arrest

Mary was moved between various castles, including Tutbury, Sheffield, and Chartley, under the watch of Sir Amyas Paulet, a strict Puritan who despised her.

- Restrictions: She was denied visitors, had limited correspondence, and was forbidden from practicing Catholicism openly.

- Luxuries: Despite her captivity, she was allowed fine clothes, books, and pets—small comforts that kept her sane.

- Health Decline: Mary suffered from rheumatism, depression, and possibly porphyria (a blood disorder), which weakened her over time.

Example: Mary embroidered intricate tapestries during her imprisonment, some of which survive today. This was one of the few creative outlets she had.

Actionable Insight: Even in confinement, finding small joys and hobbies can help maintain mental resilience—a lesson applicable to anyone facing long-term stress.

The Babington Plot: The Trap That Sealed Her Fate

Mary’s desperation for freedom led her to correspond with Catholic conspirators, including Anthony Babington, who plotted to assassinate Elizabeth.

- The Coded Letters: Mary’s letters were smuggled in beer barrels and written in cipher. However, Elizabeth’s spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham, intercepted and decoded them.

- The Fatal Correspondence: In 1586, Mary wrote a letter approving the plot, unaware that Walsingham had set a trap.

- Arrest and Trial: The letters were used as evidence in her trial, where she was found guilty of treason.

Step-by-Step Tip: Mary’s downfall was accelerated by her own words. In high-stakes situations, discretion is key—modern leaders should avoid written communications that could be used against them.

The Trial: A Queen Condemned

Mary’s trial was a foregone conclusion—Elizabeth’s advisors wanted her dead, but Elizabeth hesitated, fearing the precedent of executing a anointed queen.

- The Charges: Mary was accused of plotting Elizabeth’s assassination and conspiring with foreign powers (Spain).

- Mary’s Defense: She denied the charges, arguing that she was not an English subject and thus could not commit treason. She also appealed to Elizabeth as a fellow queen.

- The Verdict: The court found her guilty, and Elizabeth signed the death warrant—though she claimed she never intended it to be carried out.

Example: Mary wore a red dress (the color of Catholic martyrs) to her execution, defiantly embracing her fate.

Actionable Insight: Mary’s trial shows how legal systems can be manipulated for political ends. Leaders should ensure fair trials and due process, even for their enemies.

The Execution: A Queen’s Final Moments

Mary’s execution was a spectacle of dignity, defiance, and tragedy. Her death shocked Europe and cemented her legend.

The Last Days: Preparing for Death

In the days leading up to her execution, Mary prepared herself spiritually and emotionally.

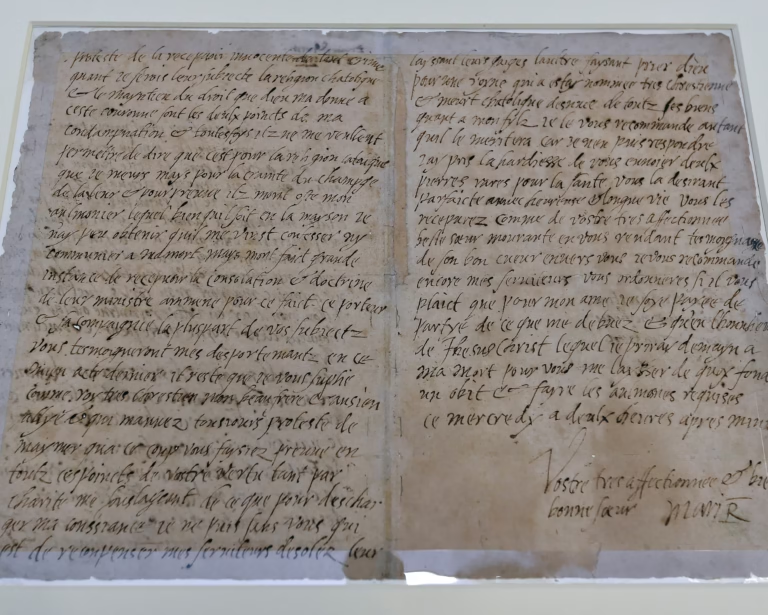

- Final Letters: She wrote farewell letters to King Henry III of France and her son, James VI, urging him to remain Protestant (a bitter irony, given her Catholic faith).

- Confession and Prayer: She confessed her sins to a Catholic priest and prayed for forgiveness.

- The Execution Outfit: She chose a red petticoat, black gown, and white veil—symbolizing martyrdom, mourning, and purity.

Step-by-Step Tip: Mary’s calm acceptance of death is a lesson in facing adversity with grace. In difficult times, focusing on legacy and faith can provide strength.

The Execution: A Bloody Affair

On February 8, 1587, Mary was beheaded at Fotheringhay Castle.

- The First Blow: The executioner missed her neck and struck her shoulder, causing her to cry out in pain.

- The Second Blow: He struck again, but the head did not sever cleanly. He had to saw through the remaining sinew.

- The Aftermath: When the executioner lifted her head, her wig fell off, revealing gray hair—a shocking detail that humanized her in the eyes of witnesses.

Example: Mary’s little dog, a Skye terrier, was found hiding under her skirts after the execution, covered in her blood.

Actionable Insight: Mary’s execution was botched and brutal, a reminder that even the most powerful are vulnerable in death. Leaders should treat their enemies with dignity, as cruelty often backfires in the long run.

The Burial: A Queen’s Resting Place

Mary’s body was embalmed and placed in a lead coffin, but her burial was delayed for months due to Elizabeth’s indecision.

- First Burial: She was buried in Peterborough Cathedral in a simple ceremony.

- James VI’s Request: When her son became King James I of England, he had her body moved to Westminster Abbey in 1612, where she was reburied in a grand tomb near Elizabeth I.

- Legacy: Today, her tomb is one of the most visited in Westminster Abbey, a testament to her enduring fame.

Step-by-Sight Tip: Mary’s posthumous rehabilitation shows how legacy can be reshaped over time. Leaders should consider how history will remember them—not just their actions in life.

The Legacy: A Queen Remembered

Mary Queen of Scots’ life was a tragedy of Shakespearean proportions, but her legacy transcends her failures. She remains a symbol of resilience, romance, and rebellion.

The Myth vs. The Reality

Mary’s story has been romanticized and distorted over the centuries.

- The Romantic Heroine: Novels, plays, and films (like Schiller’s Mary Stuart and the 2018 film Mary Queen of Scots) portray her as a tragic, doomed beauty.

- The Political Failure: Historians debate whether she was a victim of circumstance or a reckless ruler who brought about her own downfall.

- The Catholic Martyr: To Catholics, she was a symbol of resistance against Protestantism. To Protestants, she was a dangerous schemer.

Actionable Insight: Mary’s story teaches us that history is written by the victors. When studying historical figures, seek multiple perspectives to avoid bias.

The Impact on British History

Mary’s life shaped the future of Britain in unexpected ways.

- The Union of Crowns: Her son, James VI of Scotland, became James I of England in 1603, uniting the two kingdoms under one monarch.

- The Elizabethan Settlement: Mary’s execution strengthened Elizabeth’s rule and solidified Protestantism in England.

- The Jacobite Cause: Centuries later, Catholic rebels (Jacobites) used Mary’s memory to challenge Protestant rule, leading to uprisings like the 1745 rebellion.

Example: The Jacobite risings (1688–1746) were partly inspired by Mary’s Catholic legacy, showing how historical grievances can fuel future conflicts.

Step-by-Step Tip: Mary’s influence on British history shows how personal dynasties shape nations. Leaders should consider the long-term consequences of their actions.

Lessons from Mary’s Life

Mary’s story offers valuable lessons for modern leaders, historians, and anyone facing adversity.

- The Danger of Emotional Decisions: Mary’s marriages to Darnley and Bothwell were personal choices that destroyed her politically.

- The Power of Perception: Her reputation was weaponized against her—public image matters.

- Resilience in Captivity: Even in 19 years of imprisonment, she never stopped fighting for her freedom.

- The Cost of Ambition: Her desire for the English throne led to her execution—know when to compromise.

- Legacy Over Longevity: Mary ruled for only 6 years but left a lasting impact—focus on what truly matters.

Final Thought: Mary Queen of Scots’ life was a cautionary tale, but also a story of courage. Her strength in the face of adversity continues to inspire, proving that even in failure, there is dignity.